Temporalità digitale – La responsabilità dell’Interaction Design nell’alienazione digitale

DOI:

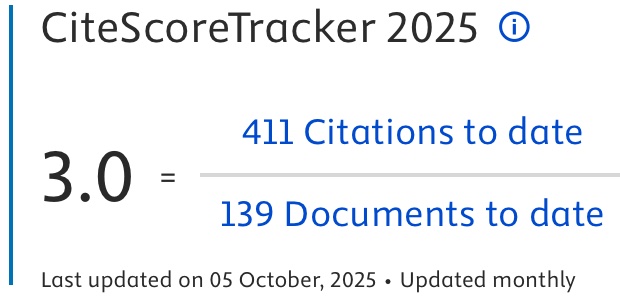

https://doi.org/10.69143/2464-9309/17232025Parole chiave:

design dell’interazione, benessere digitale, temporalità, decadimento cerebrale, alienazione digitaleAbstract

La temporalità degli ecosistemi digitali ha ridefinito il modo in cui percepiamo e organizziamo il tempo, privilegiando efficienza e produttività. Le tecnologie digitali, progettate per accessibilità costante, disconnettono l’esperienza umana dai ritmi naturali e generano un tempo inabitabile, coreografato da ‘tecnoperformance temporali’ che impongono gesti e ritmi frenetici, con impatti psicologici rilevanti, comportando l’introduzione del ‘benessere digitale’ come dimensione chiave della salute mentale. L’Interaction Design, come interprete della relazione tra umani e digitale, ha la responsabilità di affrontare queste dinamiche, ripensando la progettazione come pratica etica e consapevole del tempo. Il contributo propone una revisione critica della letteratura in design e scienze sociali, per valutare in che modo le pratiche di Interaction Design influenzino o possano mitigare l’alienazione temporale.

Info sull'articolo

Ricevuto: 15/03/2025; Revisionato: 24/04/2025; Accettato: 03/05/2025

Downloads

##plugins.generic.articleMetricsGraph.articlePageHeading##

Riferimenti bibliografici

Agre, P. E. (2001), “Welcome to the always-on world”, in IEEE Spectrum, vol. 38, issue 1, pp. 10-13. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1109/6.901159 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Al-Mansoori, R. S., Al-Thani, D. and Ali, R. (2023), “Designing for digital wellbeing – From theory to practice a scoping review”, in Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, vol. 2023, issue 1, article 9924029, pp. 1-24. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1155/2023/9924029 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Baron, N. S. (2010), Always on – Language in an online and mobile world, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Bolter, J. D. (1984), Turing’s man – Western culture in the computer age, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Brubaker, R. (2020), “Digital hyperconnectivity and the self”, in Theory and Society | An Interdisciplinary Social Science Journal, vol. 49, pp. 771-801. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1007/s11186-020-09405-1 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Castells, M. (1996), The rise of the network society, Blackwell, Cambridge, MA.

Cerretani, P. (2012), “Tempo e comunicazione”, in Arecco, F. (ed.), Tempo al tempo – Riflessione corale sul concetto di tempo, Mimesis, Milano, pp. 415-418. [Online] Available at: mimesisedizioni.it/download/12507/7b519f6781f2/tempo-al-tempo.pdf [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Coeckelbergh, M. (2022), Digital technologies, temporality, and the politics of co-existence, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17982-2 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Eriksen, T. H. (2001), Tyranny of the moment – Fast and slow time in the information age, Pluto Press, London.

Fabbri, M. (2020), “Preadolescenti onlife – Educare alla cittadinanza digitale”, in MeTis | Mondi educativi – Temi, Indagini, Suggestioni, vol. 10, issue 1, pp. 139-161. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.30557/MT00116 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Firth, J. A., Torous, J. and Firth, J. (2020), “Exploring the impact of internet use on memory and attention processes”, in International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 17, issue 24, article 9481, pp. 1-12. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249481 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Floridi, L. (2015), The Onlife Manifesto – Being human in a hyperconnected era, Springer, Cham. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04093-6 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Fuchsberger, V., Murer, M. and Tscheligi, M. (2015), “Time and design – seven sensitivities”, in Verplank, B. and Ju, W. (eds), TEI 2015 – Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Stanford, California, January 15-19, 2025, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp. 581-586. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1145/2677199.2687911 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Hallnäs, L. and Redström, J. (2001), “Slow technology – Designing for reflection”, in Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, vol. 5, pp. 201-212. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1007/PL00000019 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Han, B.-C. (2022), Le non cose – Come abbiamo smesso di vivere il reale, Einaudi, Torino.

Hendon, Z. and Massey, A. (eds) (2019), Design, history and time – New temporalities in a digital age, Bloomsbury Publishing, London.

Henrich, J. (2022), WEIRD – La mentalità occidentale e il futuro del mondo, Il Saggiatore, Milano.

Hesselberth, P. (2017), “Discourses on disconnectivity and the right to disconnect”, in New Media and Society, vol. 20, issue 5, pp. 1994-2010. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1177/1461444817711449 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Khan, A. H., Heiner, S. and Matthews, B. (2019), “Disconnect – A proposal for reclaiming control in HCI”, in Brewster, S. and Fitzpatrick, G. (eds), CHI’19 Extended abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, Scotland, May 4-9, 2019, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, article LBW1319, pp. 1-6. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1145/3290607.3313048 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Kitchin, R. (2023), Digital Timescapes – Technology, temporality and society, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Kubler, G. (1962), The shape of time – Remarks on the history of things, Yale University Press, New Haven. [Online] Available at: monoskop.org/ images/8/87/Kubler_George_The_Shape_of_Time_Remarks_on_the_ History_of_Things.pdf [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Lee, J. and Zarnic, Z. (2024), The impact of digital technologies on well-being – Main insights from the literature. [Online] Available at: oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/11/the-impact-of-digital-technologies-on-well-being_848e9736/cb173652-en.pdf [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Lyngs, U., Lukoff, K., Csuka, L., Slovák, P., Van Kleek, M. and Shadbolt, N. (2022), “The Goldilocks level of support – Using user reviews, ratings, and installation numbers to investigate digital self-control tools”, in International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, vol. 166, article 102869, pp. 1-13. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2022.102869 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Mazé, R. (2007), Occupying time – Design, technology, and the form of interaction, Doctoral Dissertation Series, no 2016/16, Malmö University – Blekinge Institute of Technology, Axl Books, Stockholm. [Online] Available at: diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:836366/FULLTEXT01.pdf [Accessed 27 April 2025].

McLuhan, M. (1964), Understanding media – The extensions of man, McGraw-Hill, New York. [Online] Available at: designopendata.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/understanding-media-mcluhan.pdf [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Mirbabaie, M., Stieglitz, S. and Marx, J. (2022), “Digital detox”, in Business and Information Systems Engineering, vol. 64, issue 2, pp. 239-246. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1007/s12599-022-00747-x [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Newport Institute (2024), Brain rot – The impact on young adult mental health. [Online] Available at: newportinstitute.com/resources/co-occurring-disorders/brain-rot/ [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Nguyen, N. (2020), “Doomscrolling – Why we just can’t look away – Primal instincts often drive our obsession with stressful news, and social-media platforms are designed to keep us hooked”, in The Wall Street Journal, 07/06/2020. [Online] Available at: wsj.com/articles/doomscrolling-why-we-just-cant-look-away-11591522200 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Oxford University Press (2024), ‘Brain rot’ named Oxford Word of the Year 2024. [Online] Available at: corp.oup.com/news/brain-rot-named-oxford-word-of-the-year-2024/ [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Özpençe, A. İ. (2024), “Brain rot – Overconsumption of online content – An essay on the publicness of social media”, in Journal of Business Innovation and Governance, vol. 7, issue 2, pp. 48-60. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.54472/jobig.1605072 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Petridis, P., Stouraitis, E. and Patiniotis, M. (2022), “Many times – The perception of temporality in digital environments”, in Entanglements, vol. 5, issue 1/2, pp. 35-49. [Online] Available at: users.uoa.gr/~mpatin/Papers/Many%20times.pdf [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Pond, P. (2024), Digital media and the making of network temporality, Routledge, London.

Pschetz, L. and Bastian, M. (2018), “Temporal design – Rethinking time in design”, in Design Studies, vol. 56, pp. 169-184. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2017.10.007 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Pschetz, L., Bastian, M. and Speed, C. (2016), “Temporal design – Looking at time as social coordination”, in Lloyd, P. and Bohemia, E. (eds), Proceedings of DRS2016 – Design + Research + Society – Future-Focused Thinking, Brighton, United Kingdom, June 27-30, 2016, Design Research Society, London, pp. 2109-2122. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.21606/drs.2016.442 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Rahm-Skågeby, J. and Rahm, L. (2021), “HCI and deep time – Toward deep time design thinking”, in Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 37, issue 1, pp. 15-28. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1080/07370024.2021.1902328 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Schmuck, D. (2020), “Does digital detox work? Exploring the role of digital detox applications for problematic smartphone use and well-being of young adults using multigroup analysis”, in Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, vol. 23, issue 8, pp. 526-532. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0578 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Stäheli, U. and Stoltenberg, L. (2022), “Digital detox tourism – Practices of analogisation”, in New Media and Society, vol. 26, issue 2, pp. 1056-1073. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1177/14614448211072808 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Statista (2024), Number of internet users worldwide from 2005 to 2024. [Online] Available at: statista.com/statistics/273018/number-of-internet-users-worldwide/ [Accessed 27 April 2025].

UN – United Nations (2015), Transforming Our World – The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, document A/RES/70/1. [Online] Available at: docs.un.org/en/A/RES/70/1 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Vacanti, A. and Leonardi, C. (2024) “Tecnologia, energia e tempo – Percorsi sperimentali per il design di tecnologie appropriate | Technology, energy, and time – Experimental paths for the design of appropriate technology”, in Agathón | International Journal of Architecture, Art and Design, vol. 15, pp. 316-323. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.19229/2464-9309/15262024 [Accessed 27 April 2025].

Virilio, P. (1997), Open sky, Verso, London.

##submission.downloads##

Pubblicato

Come citare

Fascicolo

Sezione

Categorie

Licenza

Copyright (c) 2025 Annapaola Vacanti, Michele De Chirico, Davide Crippa, Raffaella Fagnoni

TQuesto lavoro è fornito con la licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione 4.0 Internazionale.

AGATHÓN è pubblicata sotto la licenza Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CC-BY).

License scheme | Legal code

Questa licenza consente a chiunque di:

Condividere: riprodurre, distribuire, comunicare al pubblico, esporre in pubblico, rappresentare, eseguire e recitare questo materiale con qualsiasi mezzo e formato.

Modificare: remixare, trasformare il materiale e basarti su di esso per le tue opere per qualsiasi fine, anche commerciale.

Alle seguenti condizioni

Attribuzione: si deve riconoscere una menzione di paternità adeguata, fornire un link alla licenza e indicare se sono state effettuate delle modifiche; si può fare ciò in qualsiasi maniera ragionevole possibile, ma non con modalità tali da suggerire che il licenziante avalli l'utilizzatore o l'utilizzo del suo materiale.

Divieto di restrizioni aggiuntive: non si possono applicare termini legali o misure tecnologiche che impongano ad altri soggetti dei vincoli giuridici su quanto la licenza consente di fare.

Note

Non si è tenuti a rispettare i termini della licenza per quelle componenti del materiale che siano in pubblico dominio o nei casi in cui il nuovo utilizzo sia consentito da una eccezione o limitazione prevista dalla legge.

Non sono fornite garanzie. La licenza può non conferire tutte le autorizzazioni necessarie per l'utilizzo che ci si prefigge. Ad esempio, diritti di terzi come i diritti all'immagine, alla riservatezza e i diritti morali potrebbero restringere gli usi del materiale.